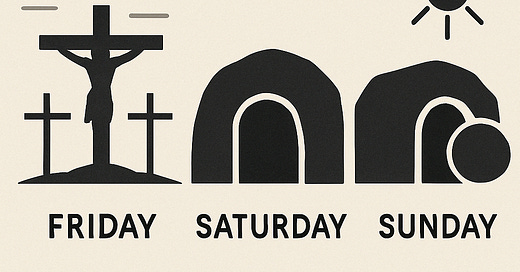

The Three-Day Mystery: Understanding the Timeline of Jesus’ Death and Resurrection

The words have echoed across centuries: “and on the third day He rose again.” For most Christians, the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ is the cornerstone of their faith—yet buried within that triumphant proclamation is a question that has puzzled both believers and skeptics alike: If Jesus was crucified on a Friday and resurrected on a Sunday, how do we account for “three days and three nights” in the tomb?

At first glance, the math seems off. Friday afternoon to Sunday morning does not appear to span three full days, let alone three days and three nights. But before we discard centuries of tradition or retreat into simplistic defenses, it is worth stepping into the world of first-century Jewish context—where counting days, reckoning time, and understanding prophetic fulfillment requires more than our modern calendar logic.

Let us begin by recognizing the source of this phrase. In Matthew 12:40, Jesus says, “For as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the whale, so shall the Son of Man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.” This verse has become a cornerstone for those who demand a literal 72-hour period between crucifixion and resurrection. But the Gospel accounts themselves, along with the Jewish understanding of time, paint a more nuanced picture.

Jewish Timekeeping: When a Day is More Than a Day

In Jewish tradition, any part of a day is counted as a whole day. This is not creative math—it was standard practice in first-century Judea. If an event happened late on Friday and concluded early on Sunday, it would still be referred to as spanning three days: Friday (Day 1), Saturday (Day 2), and Sunday (Day 3). This method of reckoning is seen throughout both the Old and New Testaments. The Talmud, for instance, confirms this inclusive reckoning of days, and we find examples in the Old Testament where part of a day is clearly treated as a full day in historical narrative and prophecy.

Thus, Friday afternoon (when Jesus died) counts as Day 1. The Sabbath (Saturday), during which His body remained in the tomb, is Day 2. And early Sunday morning—before sunrise—when the women discovered the tomb was empty, completes Day 3. While it may not satisfy our modern, hyper-precise standards of timekeeping, it fully aligns with the language and expectations of the ancient world in which the Gospels were written.

Prophetic Fulfillment, Not Chronological Precision

We must also consider the prophetic context. The phrase “three days and three nights” is not an accounting formula—it is a Hebrew idiom. It signifies a full measure of time, just as “forty days and forty nights” did for Moses on the mountain or for Elijah in the wilderness. The emphasis is not on literal hour-for-hour precision but on the theological significance of completion. Jesus was dead long enough to confirm His death, buried long enough to fulfill prophecy, and resurrected early enough to symbolize the breaking of a new day—a new covenant.

Even the early church fathers, from Augustine to Irenaeus, recognized the idiomatic nature of the language. Their focus was not on whether the timeline fit neatly into a stopwatch, but whether it fulfilled the Scriptures—and it did. Jesus’ resurrection on “the third day” is affirmed repeatedly in Luke 24:7, Acts 10:40, and 1 Corinthians 15:4. In each case, the emphasis is the third day, not three 24-hour periods.

Why Friday Still Matters

So why do Christians hold to a Friday crucifixion? The Gospel narratives themselves provide the answer. All four Gospels indicate that Jesus was crucified on the “Day of Preparation”—the day before the Sabbath. Since the Sabbath is Saturday, this points clearly to a Friday execution. Attempts to push the crucifixion earlier in the week—Wednesday or Thursday—often ignore or distort the textual markers provided by the evangelists. The early church unanimously affirmed the Friday crucifixion and Sunday resurrection not out of ignorance, but because that is precisely what the eyewitness accounts testified to.

Moreover, this timing was rich with symbolic meaning. Jesus, the true Passover Lamb (1 Corinthians 5:7), was slain just as lambs were being sacrificed for the Passover feast. He rested in the tomb during the Sabbath, echoing God’s rest after creation. And He rose at dawn on the first day of the week—ushering in the new creation.

The Faithfulness of the Third Day

Rather than a flaw in the resurrection account, the “three days” timeline reinforces the unity between prophecy, tradition, and historical witness. The tension arises not from Scripture itself, but from our modern assumptions about what constitutes a “day.” In a culture driven by clocks and calendars, we sometimes forget that ancient language was not engineered for forensic audits—it was woven with symbol, idiom, and purpose.

And so, He died on Friday. He was buried before sundown. He lay in the grave through the Passover Sabbath. And early on the third day, before the sun had risen, the stone was rolled away.

The tomb was empty.

Not because the calendar was wrong—but because the King had conquered it.